Abstract

Speaker recognition systems are playing a key role in modern online applications. Though the susceptibility of these systems to discrimination according to group fairness metrics has been recently studied, their assessment has been mainly focused on the difference in equal error rate across groups, not accounting for other fairness criteria important in anti-discrimination policies, defined for demographic groups characterized by sensitive attributes. In this paper, we therefore study how existing group fairness metrics relate with the balancing settings of the training data set in speaker recognition. We conduct this analysis by operationalizing several definitions of fairness and monitoring them under varied data balancing settings. Experiments performed on three deep neural architectures, evaluated on a data set including gender/age-based groups, show that balancing group representation positively impacts on fairness and that the friction across security, usability, and fairness depends on the fairness metric and the recognition threshold.

Motivation

Speaker recognition systems are increasingly adopted in online and onlife applications to confirm or refute a user's identity based on voice characteristics. While these systems have achieved impressive accuracy using deep neural networks (X-Vector, ResNets), recent literature has uncovered algorithmic discrimination. Previous fairness assessments focused mainly on the difference in equal error rate across groups, not accounting for other fairness criteria important in anti-discrimination policies.

Research Questions

- RQ1: How do fairness metrics change under different training data balancing settings?

- RQ2: What is the impact of the recognition threshold on the trade-off between fairness, security, and usability?

Fairness Metrics

We operationalized several group fairness definitions for speaker verification:

- Demographic Parity (DP): The likelihood of being positively recognized should be the same regardless of group membership

- Equal Opportunity (EOpp): All demographic groups should have equal true positive rates

- Equalized Odds (EOdd): Demographic groups should have equal rates for both true positives and false positives

Experimental Setup

- Models: X-Vector, ResNet-34, ResNet-50

- Dataset: FairVoice with gender and age-based groups

- Balancing: Unbalanced (NB) vs. User-based balanced (UB) training sets

- Security levels: EER and FAR 1%

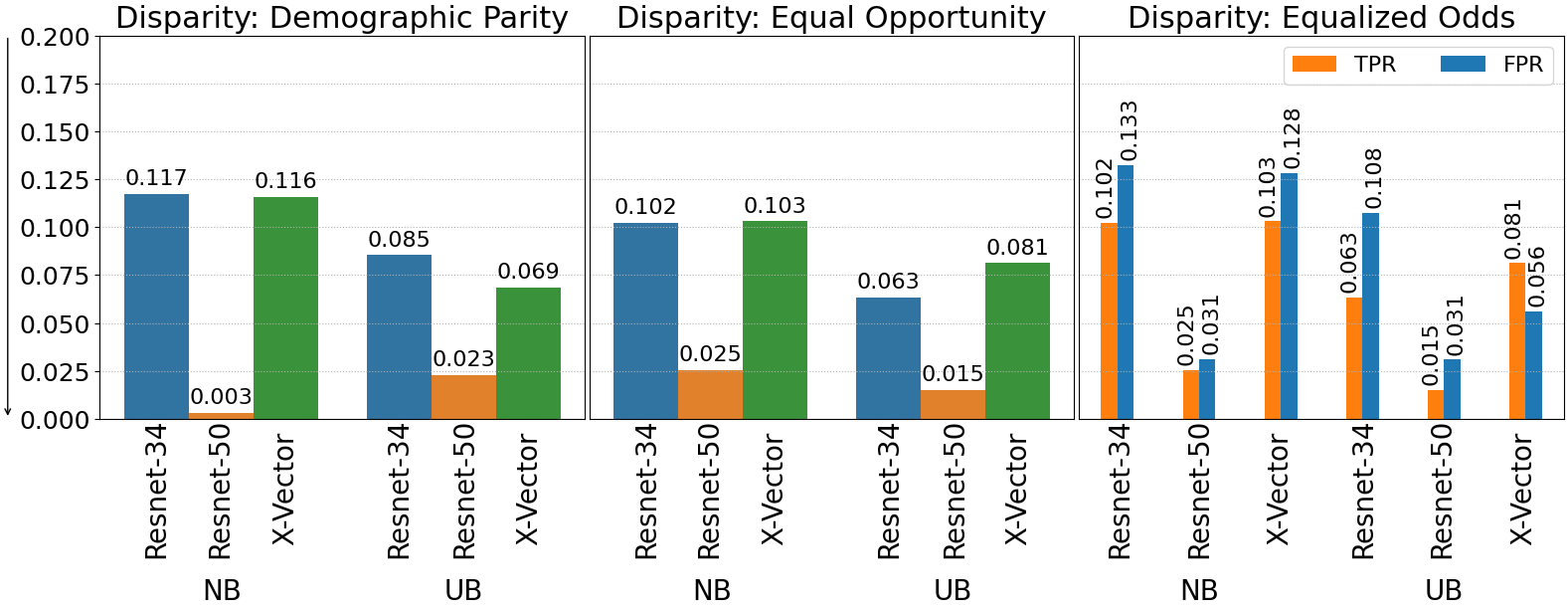

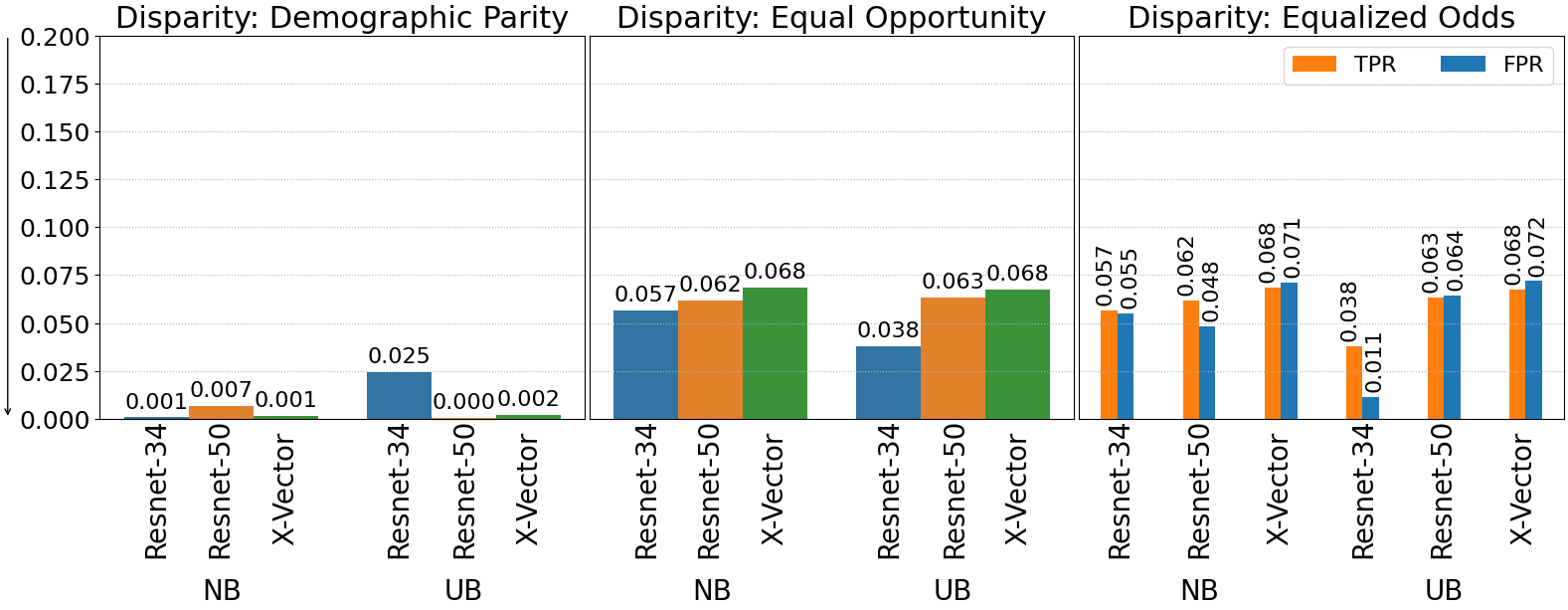

RQ1: Impact of Data Balancing on Fairness

Balancing users across demographic groups often helps mitigate unfairness. The disparities between males and females are mitigated for all models under almost all fairness metrics. ResNet-34 is influenced the most by data balancing, followed by X-Vector. Surprisingly, ResNet-50 tends to be fairer on gender-based groups regardless of balancing.

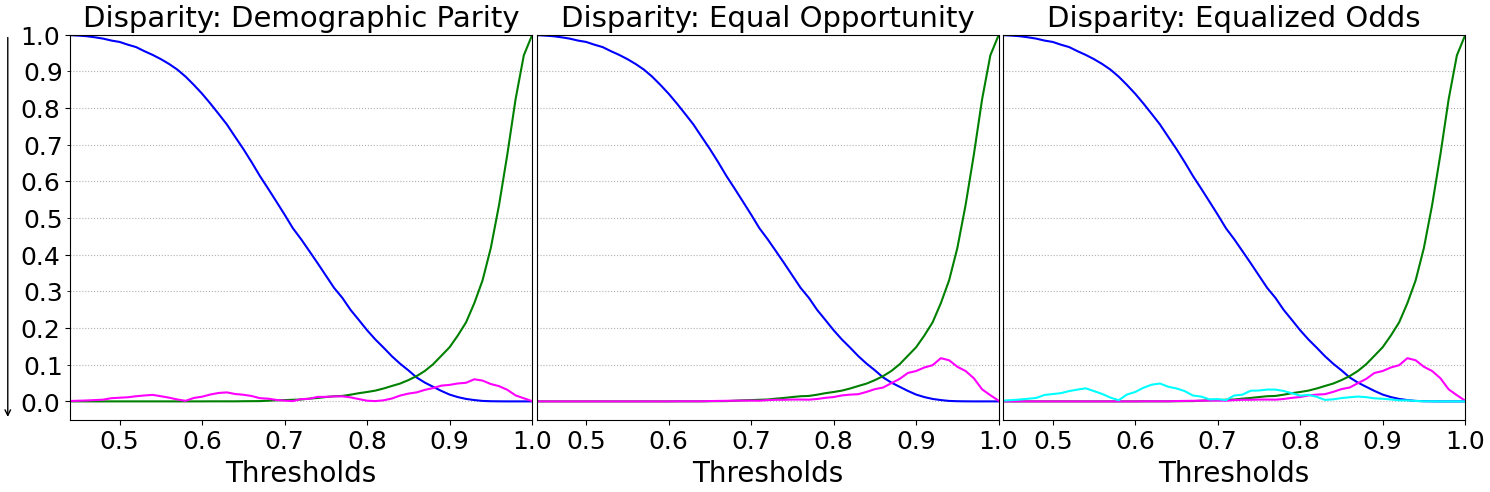

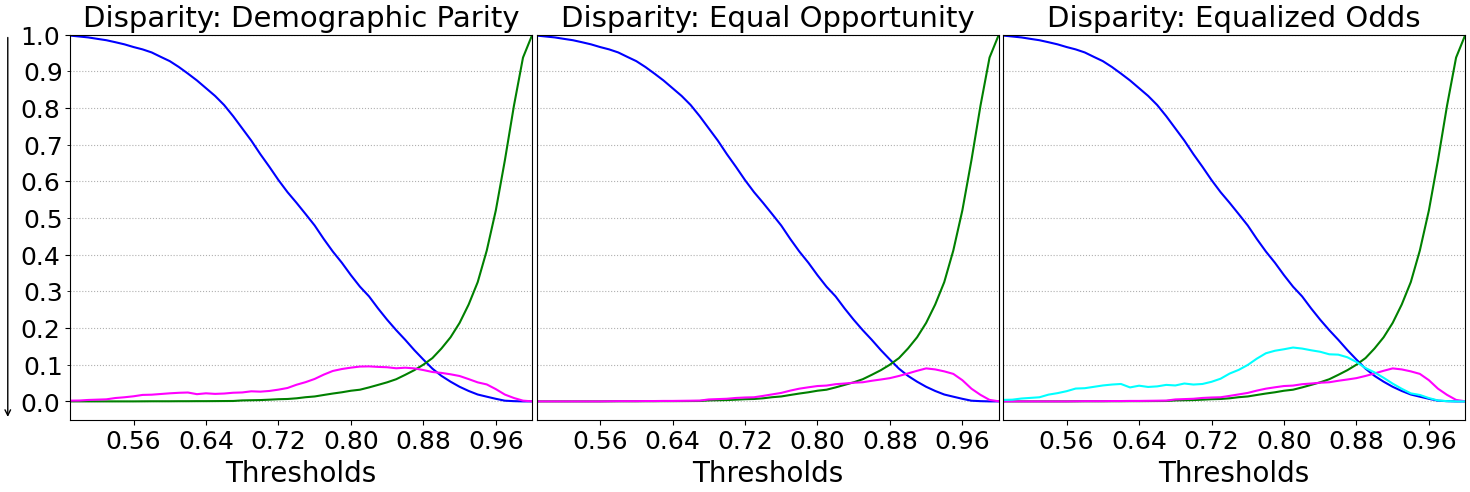

RQ2: Impact of Recognition Threshold

For almost all settings, the disparity scores show their peaks nearby the EER and FAR 1% security levels. This suggests that common operational thresholds may coincide with regions of higher unfairness.

Main Findings

- Balancing helps fairness: User-based balancing across demographic groups positively impacts fairness metrics

- Architecture matters: Different architectures respond differently to balancing - ResNet-34 benefits the most

- Threshold-fairness relationship: Fairness disparity peaks near common security thresholds (EER, FAR 1%)

- Multiple metrics needed: A single fairness metric is insufficient; different notions capture different aspects of discrimination

- Trade-offs exist: The friction across security, usability, and fairness depends on the fairness metric and recognition threshold

BibTeX

@inproceedings{fenu21_interspeech,

author = {Gianni Fenu and Mirko Marras and Giacomo Medda and Giacomo Meloni},

title = {Fair Voice Biometrics: Impact of Demographic Imbalance on Group Fairness in Speaker Recognition},

booktitle = {Proc. Interspeech 2021},

pages = {1892--1896},

year = {2021},

doi = {10.21437/Interspeech.2021-1857}

}